Golden Ages of Civilization

Friday 10 November 2023

Last week I mentioned I was reading Clive Bell’s Civilization: An Essay (I’ve finished the book now; it’s an easy read), and last week I discussed his method focusing on particular instances of “higher” civilizations. This book is now just a few years shy of its centenary, and it’s still an interesting read. Perhaps for any discipline not yet having converged upon a scientific research program (a paradigmatic stage, in Kuhn’s terminology), even hundred year old books can be helpful, whereas a hundred year old book on physics would be mostly of merely historical interest. One aspect of the book that wouldn’t go over well today is Bell’s repeated appeal to “higher” civilizations; even in biology, and despite Darwin’s many uses of “the higher animals,” it is now longer considered good form to make these hierarchical distinctions even in the natural sciences, let alone the social sciences; I have discussed this many times, and regular readers know my views on this. However, Bell also frequently uses “Golden Age” to refer to these paragons of civilization, as he also calls them, and this puts the matter in a slightly different light. Historians today still use “Golden Age” occasionally, even when they have largely abandoned “Dark Age” (Bell, by the way, wrote that, “in our hearts we know that the dark ages were dark” p. 123).

There have been many who have thought about civilizations from the perspective of their decline, decay, and collapse, but rather fewer, I think, who have approached civilization from the perspective of Golden Ages. This statement, however, requires an important qualification: historical works that understandably focus on the flourishing of a given civilization implicitly are draw to a Golden Age as the greatest exemplar of that civilization. In this way, then, much historical writing has implicitly been writing about Golden Ages, but a theoretical interest in Golden Ages is rather less common, and, in fact, I cannot think of an example (which does not mean that there are no such examples of theoretical interest in civilizational Golden Ages, only that I am ignorant of them).

We can think of Golden Ages as the counterpart of Dark Ages: a civilization ascends to a Golden Age, and descends into a Dark Age: both are deviations from the mean condition, with the mean condition of civilization being perhaps more stable and enduring — but not necessarily so. There seems to be an asymmetry here: Golden Ages are relatively brief, while Dark Ages can be stable and protracted — as protracted as, if not more protracted than, the mean condition. A purely theoretical conception of civilization (something I hinted at last week) would be equally interested in Golden Ages, the mean condition, and Dark Ages, insofar as all of these stages of development are expressions of civilization, but this is an occasion for another qualification. “Golden Age” is not only used to refer to peaks on the moral landscape of civilization (to borrow a simile from Sam Harris), but also to refer to a condition prior to, or even disconnected or apart from, civilization.

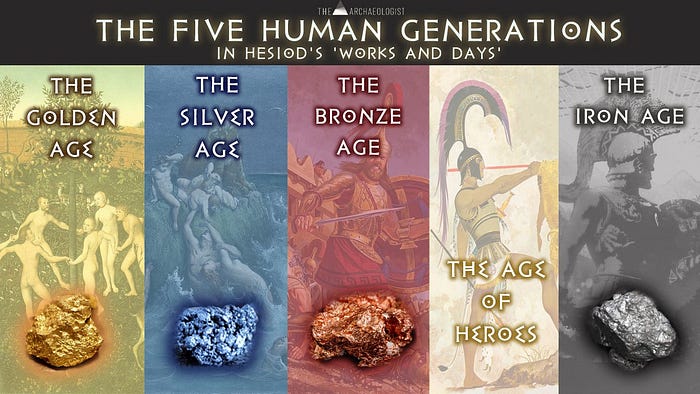

In Hesiod’s famous taxonomy of the Ages of Man, first there was a Golden Age, then the Silver, Bronze, Heroic, and Iron Ages. Further, in a loosely related ancient Greek tradition, there is the idea of Arcadia as a pastoral paradise of shepherds guarding their flocks while reciting poetry and playing pan pipes. Virgil’s Eclogues are set in this kind of idealized landscape. A further twist delivers us from the merely archaically strange to the contradictory. In many paintings that purport to represent the ideal Arcadian landscape, we see classical ruins in the distance (for example, in Thomas Cole’s painting L’Allegro, which is distinct from his The Arcadian State, but repeats many of its motifs; The Arcadian State is part of Cole’s sequence of paintings known as The Course of Empire), implying that this is an idealized pastoralism that nevertheless plays out after the collapse of ancient civilization, in other words, this is an Arcadia of the Dark Ages.

Perhaps it could be agreed that both Dark Ages and Arcadia represent lower levels of social complexity, or, if you like, lower levels of civilization, or no civilization at all. We can posit an Arcadia that is outside time, or that is a pre-civilized state, but a Dark Age implies a previous condition of civilization — it might be a civilization that has simply fallen away from the mean condition, or it might be a civilization that attained to a Golden Age, and then catastrophically collapsed, the Golden Age being unsustainable, down to a level below the mean condition, into a Dark Age. We can further posit that, if the complexity of the society does not recover, and further decays, that civilization will cease altogether, and a Dark Age will give way to a renewed savage state — or a new Arcadia, if one wishes to be tendentious about this developmental sequence.

Taking Dark Ages as the counterpart of Golden Ages, the above developmental sequence can be contrasted to a developmental sequence of a civilization passing to higher states of complexity, so that the mean state passes into a Golden Age. Does the Golden Age then pass into a further state of increased complexity? Is that possible? I have been using the admittedly awkward term “transcendence” to indicate when a civilization passes over into a qualitatively different state. There are only two clear-cut examples of macrohistorical transcendence: the of origins of civilization itself (which, in a narrow sense, is not an instance of a civilization passing into a qualitatively different state, so we could say that there is only one true macrohistorical transcendence), and the passage from agricultural civilization to industrialized civilization. If we eventually make the transition from industrialized civilization to spacefaring civilization, then that will be another qualitative transcendence. So, the question posed by the above discussion is whether a transcendence event can obtain in a Golden Age, or whether (as seems likely to me) a transcendence event arises from a condition of social unrest and historical turbulence. A Golden Age to me implies a kind of quietude and repose, but if we think of a Golden Age as a period of energetic activity (Kenneth Clark speaks in this vein), then it is easy to imagine that a transcendence event could obtain in (or as a consequent of) a Golden Age. The historical record is interestingly ambiguous.

One of the three higher civilizations (or “paragons”) identified by Bell is eighteenth century France, or, we might say, France during the Enlightenment (but before the revolution, which is a direct consequence of the Enlightenment). Industrialization did, in fact, begin at the end of the eighteenth century, but it began in England rather than France, and, when it crossed the channel, it achieved its greatest development in Germany rather than in France. One could argue loosely from this high state of civilization in France during the Enlightenment for its impact upon the whole of European society (which is true), noting both that the high civilization of Enlightenment France gives way to the chaos of the French Revolution, and then the Napoleonic Wars, even as the industrial revolution was getting underway elsewhere. Moreover, if we count France as a part of European civilization (which is accurate), then we can say that a high state of civilization existed in one part of European civilization, and was immediately followed by a transcendence event elsewhere in Europe. This is fair enough, but does it settle the question? Not decisively.

The fact that we have only this single clear-cut instance of a qualitative change in civilization means that we can’t helpfully generalize from it, in the same way that we shouldn’t generalize from life on Earth — the only instance of life known to us — to life in the universe. We can, however, take a step down and consider major changes in civilization that don’t quite rise to the qualitative change wrought by the industrial revolution, and see if these second-tier transcendence events (such as written language, the Axial Age, or the scientific revolution) seem to follow from Golden Ages or if they are born out of chaos.

Another interesting aspect of Golden Ages is that they can appear at different stages in the development of a civilization, and so represent a deviation from a deterministically understood developmental trajectory of a civilization. I’ve also been reading T. S. Eliot’s Notes Toward the Definition of Culture, in which Eliot states that:

“We have to admit, in comparing one civilisation with another, and in comparing the different stages of our own, that no one society and no one age of it realises all the values of civilisation. Not all of these values may be compatible with each other: what is at least as certain is that in realising some we lose the appreciation of others.”

On a side note, in the very next sentence Eliot explicitly affirms that, “we can distinguish between higher and lower cultures.” In any case, I think that Eliot is correct in the above claim that the values of a given civilization are differently realized by different stages in the development of a given civilization. This, in turn, means that the distinctive values of any one stage might flourish as a Golden Age, but this is not necessarily the case: a civilization might develop with or without a Golden Age at any one stage of development. Say we take a developmental sequence of the five stages of origins — development — maturity — decline — extinction (whatever number of stages we employ in an analysis is a matter of theoretical convention, so I don’t attach any special importance to this), then there are 32 permutations of civilization (two to the fifth power), since any of the five stages of development might have or not have a Golden Age. Certainly as a matter of fact and as a matter of resources available to a civilization, we will see more Golden Ages in the mature period of a civilization’s development, but we could adduce examples of the other permutations, even the most counter-intuitive of these, a Golden Age during extinction: Johan Huizinga’s well-known book The Autumn of the Middle Ages could be taken as a portrait of a Golden Age of medieval civilization even as it is going extinct.

There are (at least) two interesting consequences of viewing Golden Ages in this way: 1) we can introduce a further hierarchy among civilizations in terms of the number of Golden Ages they achieve, allowing also that a mean condition in maturity might exhibit several Golden Ages in sequence, each returning to the baseline mean condition, so we are not deterministically limited to a number of Golden Ages equal to the number of developmental stages, and 2) that these many permutations may obscure a developmental trajectory, e.g., an especially vigorous Golden Age during a civilization’s decline might be easily mistaken for a period of developmental maturity. Thus a civilization might be following a predictable developmental trajectory and yet appear to be defying that predictable developmental trajectory.

I find these consequences to be of great interest partly because of my distaste for the way the debate over cultural evolutionism has been conducted. Apart from the obvious objection that the debate is freighted with precisely the kind of moral baggage that makes it difficult to maintain scientific objectivity, the more important problem is the assumption of determinism built into (unilinear) cultural evolutionism by both its advocates and its critics. It is child’s play to formulate a version of cultural evolutionism that is not deterministic — e.g., we could posit multiple qualitatively distinct permutations of any one stage, that any one civilization might or might not experience — yet despite the obvious advantages to providing a more sophisticated way of discussing cultural evolutionism, we only get the monochromatic version, no matter how tiresome it gets. I don’t know who is so invested in the deterministic interpretation of cultural evolutionism, or why, but the familiar talking points are all-too-familiar because no one seems to want to go beyond them.

While I am going on about cultural evolutionism and moral baggage, it is interesting to imagine how differently Lewis Henry Morgan’s cultural evolutionism would have been received if he had named his stages of developmental progress Eden — Arcadia — civilization instead of savagery — barbarism — civilization, and the substitution works pretty well (albeit not perfectly), as Eden is a time before technology, roughly equivalent to savagery, while Arcadia is associated with pastoralism (with shepherds, to be specific), roughly equivalent to barbarism.

When Morgan named his stages, I doubt the terms he used were as freighted with moral baggage as they are today, or perhaps simply not so stigmatized in Morgan’s immediate milieu. Ancient Society, in which Morgan formulated and named his stages, appeared in 1877. Bell’s Civilization: An Essay appeared in 1928, and Bell quite freely uses “savagery” and “barbarism” as terms of abuse some fifty years after Morgan used them as terms of classification. Perhaps Bell did so intentionally, though he evinces no interest whatsoever in anthropology or archaeology; Bell’s is a purely belles-lettristic account of civilization, as befits the genteel conception.